As a father, I am often on the lookout for signs that my children are losing their interior freedom. Perhaps a better way to think about this is that they are not fully developing their interior freedom, as few children in history have ever come out free from the start. If you have such a child, congratulations!

Here in our household, freedom is a notion which is often celebrated but grossly misunderstood. Even the adults fall victim to this, especially if there are treats involved which an adult may find appealing (a date night, for instance). I have on many occasions found myself restricting the freedom of my children for the sake of expanding the freedom my wife and I would like to have for the evening.

But freedom is most certainly not a zero-sum game! If anything, individuals who practice freedom with generosity (and often creatively) greatly enhance the lives of those around them. So how do we make that happen with our children? Or more specifically, as our children are great big funhouse mirrors magnifying all of our best (and worst) behaviors, what sorts of behaviors do we adopt as parents to demonstrate a proper use of one’s freedom?

To begin, maybe we should define some terms. It’s a safe bet that freedom by today’s standards is the ability to do as one pleases. If I have sixty dollars and want to spend all of it on Snickers bars, then within my own personal agency I am able to do that. I’m imagining an adult walking out of a store with $60 in Snickers and the faces even my own children might make at that, but I digress.

If it isn’t acceptable for an adult, then it is also probably not acceptable for a child. I say, “probably” because there are certainly situations in which I find it perfectly OK for a child to not behave like an adult. What are they? I don’t know. Christmas day, perhaps. Or maybe when they get excited about reading Goodnight Moon for the 32nd time. As Chesterton says, “grown-up people are not strong enough to exult in monotony.”

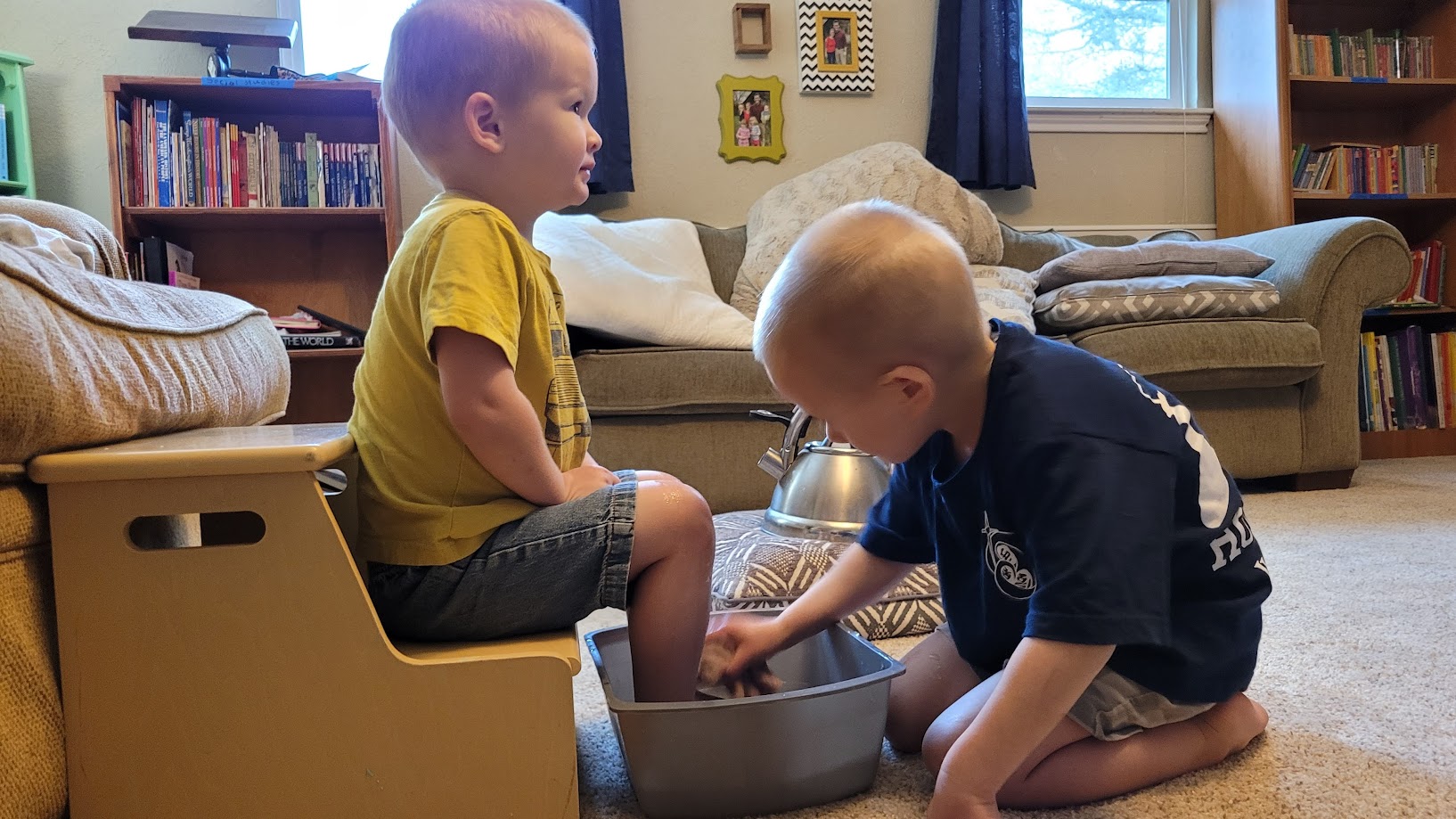

When I think about what freedom is, I can’t help but think about how to cultivate within my junior Neanderthals a sense of wonder. I can’t force them, much as I may try in moments of weakness. No one was ever beaten or harassed into genuine conversion.

So I find myself grappling with two ideals: respecting personal freedom, and developing wonder. From my imperfect point of view, I see wonder as a natural byproduct of genuine freedom which I will define as doing as you ought rather than as you want.

A simple example which supports this claim which most of us have heard is learning an instrument. We may freely hammer with abandon at the keys of a piano, but there’s certainly no freedom to be had. By extension, there is little opportunity for wonder. Masters can not only ponder deeper mysteries of their crafts, but by the skill they have built through discipline freely explore those mysteries.

Contrast that with modern freedom which states that doing as you want is the real standard. These conversations come up at work more often than I’d like when people find out I have five children. Common responses are:

“When do you sleep?”

“Do you ever have time for yourself?”

“I could never do that. I love being able to do what I want.”

“Did you mean to have that many?”

(protracted, concerned silence)

They usually become slack jawed when I mention that we are on the low end in our circle of friends.

Putting aside the fact that these questions pull no punches in terms of suggesting that I have too many kids and that my obvious response should be, “When should I have stopped, and therefore which children do you recommend I get rid of?”, what is really being conveyed is an admission of slavery. In particular response number three which I have heard on multiple occasions in various forms.

“But how, Jonathon, am I supposed to teach my four-year-old real freedom?”

Well, I don’t know to be honest. Your children are not my children, and so your methods will need to be tailored to suit your romping rugrats. What I’ll talk about instead are two things:

1) What we consider our ideal (i.e. what we strive to do)

2) What we ultimately do (out of convenience, necessity, or forgetfulness)

I’ll go into these in separate posts in the next few days. In the meantime, I’ll leave you with a quote from Fr. Fernando Ocariz:

“We can carry out joyfully – and not reluctantly – what we find hard, what doesn’t please us, if we do it for and with love, and therefore freely.”

Fr. Fernando Ocáriz